Housing Forward is leading the charge in the greater Dallas area against homelessness, a vexing problem that plagues many cities across the county, and in recent years the nonprofit has notched some significant victories in the effort.

Still, the organization and the coalition of groups it leads face deep systemic challenges that continue to feed the pipeline of economic despair fueling the growth of homelessness in the Dallas area — and across the nation. Chief among those challenges is a lack of affordable housing, according to industry sources in the Dallas area who are attempting to address the crisis.

As of November this year, Housing Forward and the network of service organizations it coordinates (called the All Neighbors Coalition) have met an ambitious goal by finding permanent shelter for some 2,800 previously homeless individuals in Dallas and Collin counties. That has been accomplished through the Housing Forward-led R.E.A.L Time Rehousing Initiative (or rapid rehousing) — an initiative funded by federal and private dollars that was launched in October 2021 and initially sought to rehouse 2,700 individuals.

The All Neighbors Coalition is a network of more than 140 public, private and nonprofit organizations working together to address homelessness in Dallas and Collin counties — the greater Dallas area. The nonprofit Housing Forward acts as the lead agency of the coalition, overseeing a data-driven homeless-management information system; coordinating access to services within the network; and facilitating training for service providers, among other programs.

The success of the rapid rehousing program to date has attracted additional public and private funding and resulted in a new goal of housing 6,000 individuals by 2025. The expanded goal is a recognition that even as Housing Forward and its coalition of organizations devoted to solving the homelessness crisis achieve important milestones in the greater Dallas area, the scope of the problem it seeks to address also continues to expand — and demand even more attention and resources.

The reality of the nation’s homelessness problem is that the goal posts keep moving. Housing Forward’s job is to ensure the homeless are not left behind in that game by providing them the tools and assistance necessary to effectively find and compete for scarce housing.

“Some of us talk about this system being like musical chairs because there’s only so many apartments that are ready to be moved into on any given day,” said Joli Angel Robinson, president and CEO of Housing Forward. “So, if you have 10 apartments available but you have 15 people needing an apartment, the people who are most equipped, the most connected and who have a support system that may be able to help with a downpayment, to help with moving costs, or they … can go fill out an application in the middle of the day or drive around and find a unit, they are going to get to the 10 available units much faster.”

The annual Point-in-Time count of unhoused individuals in Dallas and Collin counties, a federally mandated survey nationwide, shows that despite Housing Forward’s success in coordinating housing for nearly 3,000 individuals over the past two years, the number of unhoused on the streets of greater Dallas has continued to hover between 4,100 and 4,600 since 2018.

The most recent report shows 4,244 individuals experienced homelessness in 2023 — evidence that the pipeline into homelessness in the greater Dallas area continues to evade a long-term solution, leaving Housing Forward in a position of swimming upstream against a powerful current.

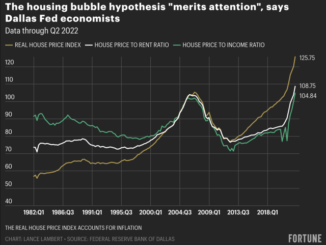

In large part, the expanding number of homeless in the Dallas area and elsewhere around the nation is being amplified by a lack of deeply affordable housing available in the market, many industry experts argue. As more and more people compete for limited housing in a fast-growth urban area like Dallas, those individuals on the economic margins of society, often a paycheck or less away from homelessness, are often left with few options other than ending up on the street — a reality playing out daily in cities nationwide.

“We have over 4,000 people experiencing homelessness, and we need more housing yesterday — and today,” Robinson said.

Adding to the problem, according to Ian Mattingly, president of Dallas-based property management company Luma Residential, is a lack of federal dollars committed to the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program — a major rental-housing subsidy program for very low-income households.

“Housing assistance was created under this administratively complicated, paternalistic system, and it’s not an entitlement, so only 2.2 million to 2.4 million families [nationwide] have access to Housing Choice Vouchers in the United States, despite the fact that if you look at it, tens of millions of people would qualify [for vouchers] under the criteria,” Mattingly said. “The real challenge is that [housing] is not an entitlement, and it is not something that the federal government has decided to put sufficient money into — to a level required to make sure housing is assessable to everyone long-term.”

The voucher program, also referred to as Section 8, is designed to cover rental costs to ensure very low-income families, the elderly and the disabled can afford housing. The HCV program has an annual budget nationwide of $27 billion, but demand for the vouchers exceeds supply by a long shot — “with only one in four eligible households receiving a voucher,” according to information released by the Cooper Housing Initiative, a private research foundation focused on the nation’s affordable-housing crisis.

“We have got to get serious about really focusing on creating and maintaining deeply affordable housing, not just for the population we serve [the unhoused), but people who are living at the margins, people that are making less than a livable wage, people that are on fixed incomes, whether that be the elderly or the disabled,” Robinson said. “…I boil it down to people that work in your city should have the opportunity to live in the city in which they work.”

Affordable-housing shortfall

David Lehde, director of governmental affairs for the Dallas Builders Association, said demand for housing and rents are both rising in the Dallas area, in part, because of rapid regional growth coupled with a dearth of available housing, particularly affordable housing.

“If newer units are more expensive, then that starts pressuring the demand on existing units as well, and that can drive up those costs,” he said. “Dallas has a lot of different types of zoning districts, and there’s discussion at City Hall about paring that down and making that more efficient and making more housing available in the city of Dallas.

“The best way to fight inflation … in prices is to build more housing.”

Jason Brown, CEO of the nonprofit Dallas City Homes (DCH), is attempting to do just that, with a focus on affordable housing. Over the past three decades, DCH has developed more than 2,400 safe and affordable rental units in some of the most distressed areas of Dallas.

Brown said developers in the affordable-housing space face many obstacles, including restrictive zoning as well as ensuring the development and operational costs pencil out — which often involves seeking government subsidies, private donations and dealing with the associated delays and red tape of the development process.

“As more and more headquarters or regional offices look at coming here [Dallas], they ask about the workforce, but our first responders, our nurses, our teachers, etc., they’re all in suburbia; they’re not living in our city,” Brown said. “So, everyone’s trying to fight for affordable housing now because they’re seeing how it impacts the city.

“Otherwise, we will have a tale of two cities — the haves and have-nots — and it’s going to be hard to have business growth or to attract national events. … So, we’re excited to see now local government and national government starting to understand [the need for affordable housing] and supporting product [development] that has a range [diversity of income], so we’re doing these real mixed-income communities now.”

James Armstrong III, president and CEO of the nonprofit Builders of Hope, which is focused on affordable-housing development in Dallas, said addressing the city’s homeless problem long-term is a “truly complex” mission “and “it’s going to require a multi-prong approach and multi-prong solutions to really move the needle.” He adds, however, that Housing Forward, under Robinson’s leadership, “has done a great job and really shown some levels of impact in recent years.”

Builders of Hope in the past has set its sights on constructing owner-occupied deeply affordable homes — developing more than 500 such homes over the past 25 years. Recently, however, Armstrong said the nonprofit unveiled plans for its first rental project — a 36-unit low-density residential development. The project is slated for West Dallas, where Armstrong said there has not been a below-market-rate multifamily development in the past 15 years.

“Dallas is becoming unaffordable due to rising housing costs, inflation, increased demand and stagnation in pay,” Armstrong said. “In fact, 52% of Dallas County renters are burdened by housing costs, which means that they pay more than 30% of their monthly income toward housing costs.

“That is a recipe for increasing the pipeline to homelessness.”

The business case for building more affordable housing in the Dallas area is underscored by a recent report by the Dallas-based Child Poverty Action Lab, which found that the city of Dallas faces a shortage of some 34,000 rental units for residents earning 50% or less of the area’s median income ($44,500 for a family of four). That housing gap left unaddressed, according to the report, is projected to increase to a nearly 86,000 units by 2030.

“Dallas needs more quality below-market multifamily housing,” Armstrong added. “Neighborhoods should be diverse, not only in income, but diverse in housing stock, in order to create that healthy cycle and that thriving neighborhood, and so we have a lot of work to do,”

Property-management realities

Stevie Jones, director of property management at Dallas-based Waller Group Property Management, said among the issues affecting the availability of existing rental properties for the homeless or extremely low-income individuals in the Dallas area is bureaucracy and red tape. He stressed that is not a problem created by Housing Forward, but rather one the nonprofit also has to navigate.

“If we were able to house [place] people quicker and get payments upfront for the first month’s rent, that would be instrumental, and I think that will help more [property] owners be willing to come onboard with some of the housing programs,” Jones said. “But bureaucracy aside, Housing Forward is an instrumental organization for the Dallas metropolitan area, and they are doing tremendous work in this community.

“Housing Forward is looking at the pool of people that are in need of housing, and they’re working with government entities or nonprofit organizations that are receiving government funds to make sure those individuals are placed in housing.”

Housing Forward has been very effective at bringing together disparate organizations that tended to operate in silos — focused on their particular slice of the [homelessness] problem, Mattingly explained. His father, Jim Mattingly, founder of Luma Residential, sits on the board overseeing Housing Forward. “They are bringing [homeless-focused organizations] together around a shared database and doing the triaging of homeless individuals to identify those partners that are going to be best-suited to provide the assistance, whether it be the housing itself or the wraparound assistance [such as mental health, addiction or job-training services].

“I think Housing Forward has done a very good job, particularly in the last few years, of building that network of relationships and going out and actively engaging with property owners, rental-housing owners, to develop relationships and to develop a network of housing providers.”

Looking forward

Armstrong of Builders of Hope said the Dallas region has all the resources necessary to solve its affordable-housing and related homelessness problem. He said the key is to effectively create “one strategic plan that includes all players involved in the cycle of ending homelessness,” and to then work together toward the common solution of decreasing homelessness in the city.

To that end, Armstrong described Housing Forward’s Robinson as a “leader who is capable of taking Housing Forward [and it’s collaborative strategy] to new heights.”

“I think we’re turning the corner,” Armstrong added. “And I think you’re going to see a lot of more collaboration within the nonprofit sector because the problem is too big for one particular group to solve.

“It’s going to take all of us, and I think we’re on that right path.”

Mattingly is equally optimistic, at least in the short-term, that the Dallas area can attain the goal of “near-zero homelessness.” He said the metro area is now on pace to deliver enough housing units to out-pace demand, which creates an opportunity for downward pressure on home prices and rents.

“Housing unaffordability is a supply and demand imbalance,” he said. “So, there is a correction underway now that is going to have a positive impact on the ability to house people.

“So, with the reduction in that demand pressure, I think there’s a window of opportunity ahead that if sufficient public and private funding can be placed toward the housing challenges, I think we can get there.”

Longer-term, however, Mattingly is less optimistic, adding that the ultimate solution to the Dallas area’s homeless problem, and the nation’s as well, will require even more federal dollars directed at the problem, including expanded funding for the existing Section 8 voucher program.

“At this point, there does not seem to be any appetite at the federal level to do what I think most economists would agree is a critical factor,” Mattingly said. “Public dollars are not allocated in the quantity that the problem demands.”

Mattingly stressed that a recent study by the National Apartment Association shows that as of 2022, fewer than 7 cents of every dollar of rent paid to property owners was “available for profit.”

“That puts us [apartment owners and managers] down in the lowest possible margin of operating businesses, down there with groceries and food production,” he said. “So, any solution to housing affordability or homelessness that disregards the fact that providing housing is not a high-profit margin industry is inevitably doomed to fail.”

Robinson said Housing Forward serves as “the backbone organization” in Dallas for coordinating and leading the response to homelessness. She stressed, however, that Housing Forward can’t solve the problem alone.

For that outcome, it will take community-wide commitment as well, Robinson added.

“We can’t lay it all at the feet of bureaucracy, or things that can be changed in that way,” she added. “It also has to do with public perception and sentiment about affordable-housing development.

“It’s about the community and the public’s appetite or willingness to have affordable-housing developments in their neighborhoods.”

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of articles highlighting Housing Forward and how what it’s doing for the local community can serve as a catalyst to affect change across the U.S. Read the first article here.