Next month in Spokane, Washington, a celebration called Expo 50 will get underway. This event will recall when a World’s Fair called Expo ’74 dramatically changed the city by revitalizing part of its downtown area, which later became the celebrated Riverfront Park.

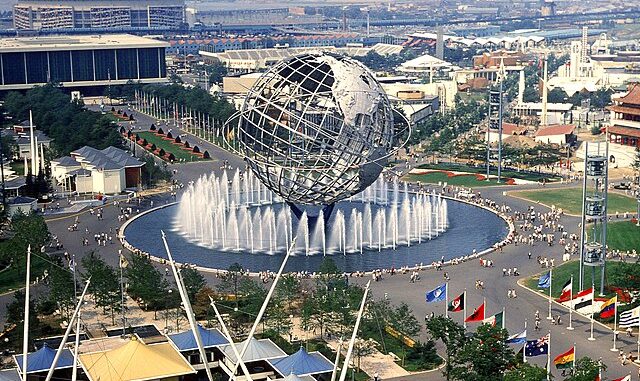

While this year’s marks the 50th anniversary of Spokane’s 1974 World’s Fair, it also marks the 120th anniversary of St. Louis’ World’s Fair, the 85th anniversary of the 1939/40 World’s Fair in New York, the 60th anniversary of the 1964/65 World’s Fair in New York, and the 40th anniversary of the World’s Fair in New Orleans – which, to date, was the last event of its kind held on American soil.

The World’s Fair concept, with its mix of educational and entertainment pavilions from different countries and corporations, has not disappeared – Dubai hosted its pandemic-delayed Expo 2020 from October 2021 to March 2022 and Osaka, Japan, will welcome the world to its event beginning in April 2025.

Some World’s Fairs presented audacious breakthroughs in housing design, most notably the Homes of Tomorrow Exhibition at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair and architect Moshe Safdie’s innovative Habitat 67 apartment complex at Montreal’s Expo 67. Some pavilions from previous fairs found new life as commercial property or government buildings.

Would it make sense to bring the World’s Fair back to the U.S. as a vehicle to help spur economic and property development? To discuss this idea, we spoke with Charles Pappas, senior writer at Exhibitor magazine and author of “Flying Cars, Zombie Dogs, and Robot Overlords: How World’s Fairs and Trade Expos Changed the World.”

Many Americans have fond memories of attending World’s Fairs in this country and overseas, but from an economic perspective some of these events were notorious for being financial flops – New York in 1964/65, New Orleans in 1984 come to mind. But have there been World’s Fairs that have been economic boons for a city?

I would half agree with what you say. New Orleans was an immediate flop, even going bankrupt before the World’s Fair (aka the World Expo) was over amid allegations of financial chicanery. But its long-term effect was one of profound prosperity — because the World’s Fair was the catalyst for rehabilitating the Warehouse District (which it was placed near) and spurring the construction of the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, by some accounts the sixth-largest convention center in America. Even more impressive to me is that the convention center is estimated to have produced some $80 billion in revenue since 1984. So, short-term disaster, long-term success.

By the way, one of the reasons the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle — the Century 21 Exposition— worked so well was that it served as the catalyst to build an exhibition hall that later evolved into the Seattle Convention Center to balance a business climate where Boeing’s fortunes occasionally dipped. Or plummeted.

From a real estate and urban development perspective, have there been World’s Fairs that had a significant post-event impact on the cities that hosted them?

If you look way back in time, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago launched the City Beautiful Movement, which sought to transform cities from mere centers of economic activity—think of Chicago and its “hog butcher to the world’ aesthetic—into something that would please the eye as much as it filled the wallet (and the stomach). Cities like Washinton, D.C., San Francisco, and St. Paul, Minnesota, changed much of their skyline and building practices because of the City Beautiful movement.

The World’s Fair also spurred construction of a modern grid of roads and subways that helped put Chicago on the map as city advancing fast into the 20th century. And there were the landmark structures, like the Palace of Fine Arts, which became the Field Museum, then the Museum of Science and Industry (the Field relocated, of course) and the Art Institute, whose combined value to Chicago has to be off the charts.

The 1939/40 World’s Fair in New York led to enormous civic improvements — such as the linking of the Grand Central Parkway to the then-new Tri-Borough Bridge, and spurring the completion of what became LaGuardia Airport. These enhancements helped establish New York as the pivot of the artistic and financial universe for the next 80 years, attracting tens of millions of visitors and residents, thus drawing in tens of billions in spending and taxes.

The 2010 Expo in Shanghai saw the Chinese government pour somewhere between $50 and $90 billion into infrastructure. Dubai spent about $20 billion on its Expo 2020. A key difference beginning with the Dubai Expo, though, is now these World’s Fairs are built with the intent of retaining and repurposing their structures to endure rather than tossed into the trash. For example, the site that held the Dubai World’s Fair has been renamed Expo City and is now a space for housing, commerce, and recreation.

But of course, the best example of how a World’s Fair improved real estate is Paris. The Paris we know and love to visit is the physical memory of its seven World Expos between 1855 and 1937: the Eiffel Tower, the upgraded gardens of the Champ de Mars, the Grand Palais, the Petit Palais, the Pont Alexandre III Bridge, the Palais de Tokyo, the Musée d’Orsay, even Maxim’s restaurant owe their existence to World’s Fairs.

More recently, Minnesota made two attempts to snag a World’s Fair and bring the event back to this country. Why did they fall short, and do you think they will eventually get an expo?

The fault lies in geography. World’s Fairs now bend toward the East and the developing world. From its beginnings in 1851 the World’s Fair was almost the birthright of Western locales like London, Paris, Chicago, and New York. Later, by the late 1970s, the West begin to think of them as antiques, the province of the elderly, like the Werther’s Originals your grandmother keeps in her purse.

Yet the rest of world embraced their unrivaled power for driving economic development and exercising an armada’s worth of soft power. That’s why you’ve seen the World Expo in places like Shanghai; Yeosu, South Korea; Astana, Kazakhstan; and Dubai; and why you’ll see the next ones in Osaka, Belgrade, and Saudi Arabia. America itself may snag one but the earliest is likely to be 2035 and then I’d say the probable contenders would be Houston, Seattle, or Phoenix.

Minnesota calculated that going to the well a third time with the same theme would have little chance of success. So, it smartly pivoted to bidding for the 2031 International Horticultural Expos. They’re somewhat similar to World Expos and, ultimately, come under the same organizing body. They can be massive in size, employ unusual architecture, and draw as many as 20-plus million visitors. It’s a canny move, given the U.S. has never held an International Horticultural Expo and yet about 55 percent of the America’s 125 million households engage in gardening. It’s a perfect match of supply and demand, you might say.

Can you share your impressions of the Dubai expo? And what are hearing about the next event coming to Osaka?

Dubai was an expo that even a pandemic couldn’t stop. The entire country bought into it, with the kind of civic pride we don’t encounter much in the U.S. anymore. In just a few years it built essentially a mini-city on an 1,100-acre site that was meant to rival the reigning champs of the World Fairs – like Paris in 1889 and Shanghai in 2010. They did a superlative job. and essentially hit their pre-COVID mark of 25 million attendees, which is astounding.

The architecture was like looking at a succession of science fiction book covers – the United Arab Emirates’ pavilion was a stylized falcon with 28 movable wings that used solar power to produce electricity. The Saudi pavilion was a Guinness World Record in physical form with the world’s largest LED mirror screen display (measuring something like 1,300 square meters), the largest interactive lighting display, and the longest interactive water feature. This was “bigger is better,” Saudi-style.

The U.K.’s pavilion was built like a monster version of a conch shell. It used an AI to take words suggested by users and then stitched those words into a poem it broadcast into outer space, all based on an idea by the late Stephen Hawking. And every day there were roughly 200 robots moving over the site, used for security, food delivery, and promotion. When you were there, you felt like you were 10 years in the future.

Osaka will be smaller in scale than Dubai, which is probably just as well. Delays, caused mostly by high material and labor costs, and a bit of a labor shortage, may mean it could open a few weeks late or, more likely, it will open with several pavilions unfinished. What most worries me is that the fleet of flying cars that were to be used as taxis might be in severely limited operation. Before I shuffle off this mortal coil, I want the flying car the Jetsons promised me.