Tucked in the hills of the Hudson Valley is a 105-acre parcel of farmland that helped pave the way for modern-day homeownership in America.

And, as of this week, it’s listed with Coldwell Banker for $4.38 million — meaning a new owner stands to purchase a prime piece of history.

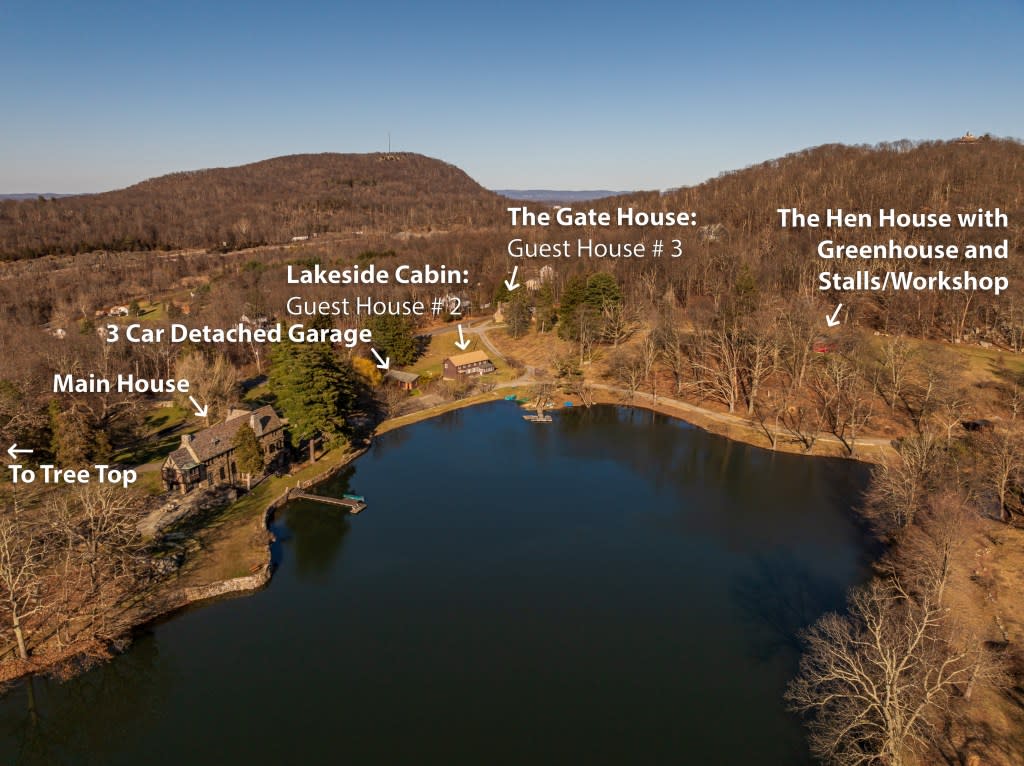

Welcome to the sprawling Willow Lake Farm in Fishkill, New York, which features a five-bedroom main house — plus three one-and-two-family guest houses.

According to property records, this land was part of a 68,000-acre parcel sold in a 1683 treaty from the Wappingers Tribe to three business associates: former New York City mayors Frances Rombouts and Stephanus Van Cortlandt, along with Rombouts’ fur-trading associate, Gulian Verplanck.

In what’s called the Rombout Patent, the three business partners received permission from King James II to own the land. The King issued 14 such patents in the area that now encompasses Putnam and Dutchess counties, with this listed property located in the latter.

Having no sons, when Rombouts died in 1691, he left 28,000 acres to his 4-year-old daughter, Catheryna Rombout (in Dutch tradition, the “s” on a surname was for sons in a family).

Rombout married British naval officer Roger Brett at age 16 and became Madam Brett, as she’s known in the Hudson Valley today.

The pair eventually ran off from New York City to live among the Native Americans on her inherited land. They had three sons before her husband died in an accident at sea.

To survive, Madam Brett turned to real estate. She stopped leasing her land and began selling off portions for cash — including the piece that would later become Willow Lake Farm.

Previously, land was owned in large quantities by wealthy families, noted Arnold Restivo, a member of the Fishkill Historical Society.

By selling off smaller, 100-acre parcels, Madam Brett allowed the New York colony’s middle class to buy property for the very first time, paving the way for print news reporters, teachers and other middle-income earners to own homes today.

“Willow Lake Farm’s history reflects the broader societal changes in property rights and ownership, particularly the shift towards more inclusive ownership,” Restivo told The Post.

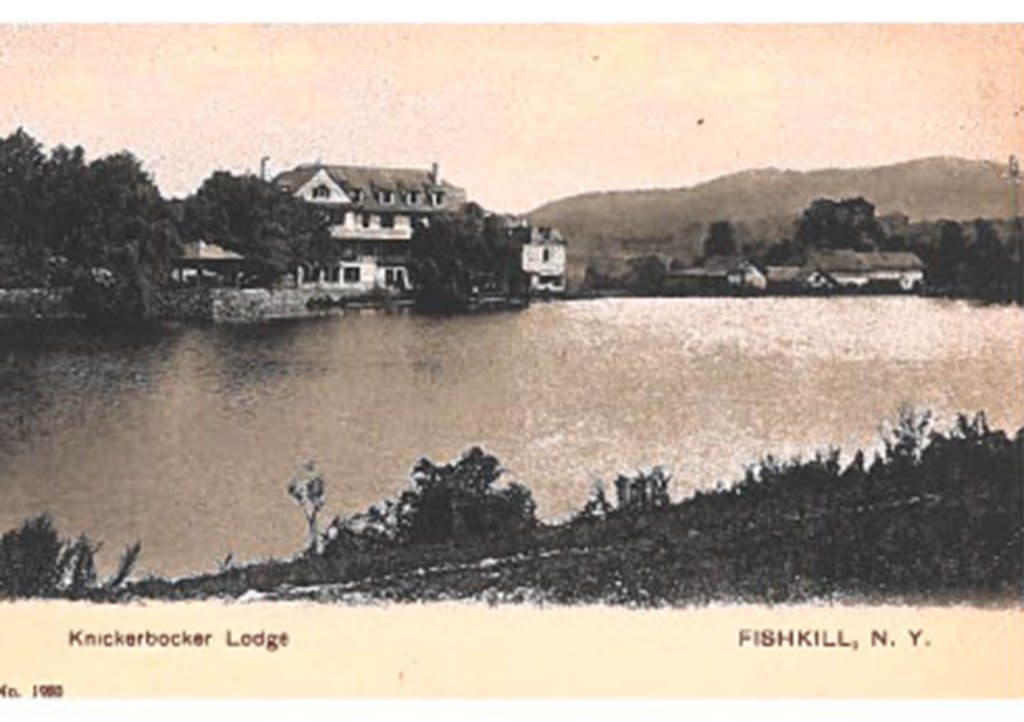

In its next chapter, the farm was developed in the late 1800s by Henry DuBois Van Wyck, a businessman who made a fortune in gold out West and later became Fishkill’s first mayor. He built the Knickerbocker Lodge which, according to an ad from the time, was an elite sanctuary designed “to add new life to the city weary, and fill the very soul of youth with free and unbounded delight.”

Ultimately, the lodge burned down in the early 1920s.

Today, passing by the stone pillars at the property’s entrance feels like a step back in time. The houses and other structures, built mostly between the 1920s and ’50s, sit on rolling hills flanked by a 5-acre carp-filled lake.

“You’re leaving everything behind when you come here,” said the current agent, Sandra “Sandi” Park of Coldwell Banker, of the farm. “You’re in a bubble.”

It’s been on and off the market several times in the last few years, but former listing agents couldn’t get the price quite right, she said.

Still, Hollywood took note of the farm’s beauty: It was recently used as a filming site for the second season of “Pretty Little Liars” on Max and the 2021 Shudder horror flick “Slapface.”

At the top of the driveway sits the 4,560-square-foot stone house built in 1924 by the husband of Planned Parenthood founder and reproductive rights activist Margaret Sanger.

It boasts four fireplaces, including one for the study in the large primary suite upstairs. Not for fans of an open layout, the interior is modeled after homes in the English countryside with designated spaces for living, dining and cooking. In the basement, mechanical and laundry rooms are tucked behind a secret bookcase door.

Celebrating its centennial this year, the home retains many historic features, including moldings and railings made from the now-endangered American chestnut tree, along with well-maintained quarter-sawn oak floors.

Original casement windows and doors are still in service, too. Their handblown leaded tiles include red, green and blue glass that refract rainbow beams on sunny days.

Outside, the house has a 100-year-old slate roof and wrought iron repurposed from Knickerbocker Lodge. Overlooking the lake is a slate patio with a bar and a waterfall built on the remains of the lodge.

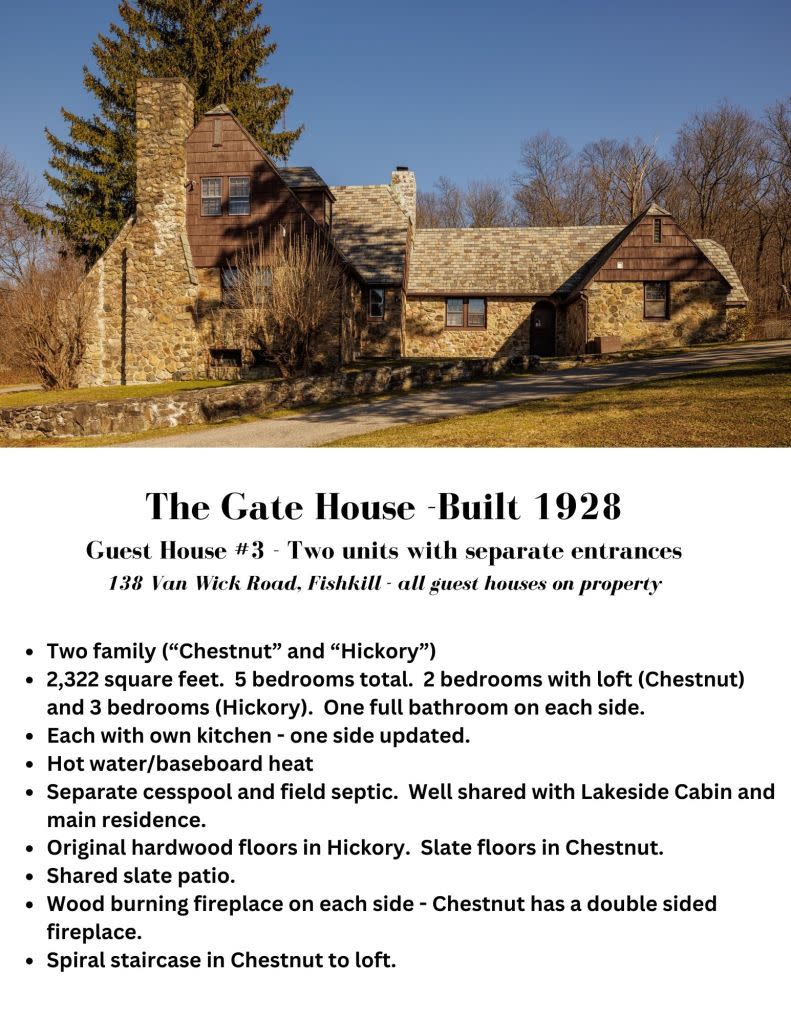

A gravel road winds around the property passing by two- and three-car garages and the guest houses, the oldest of which is the Gate House.

Built in 1928, the 2,322-square-foot two-family has separate entrances and five bedrooms total. Each side has a woodburning fireplace and a windowed kitchen.

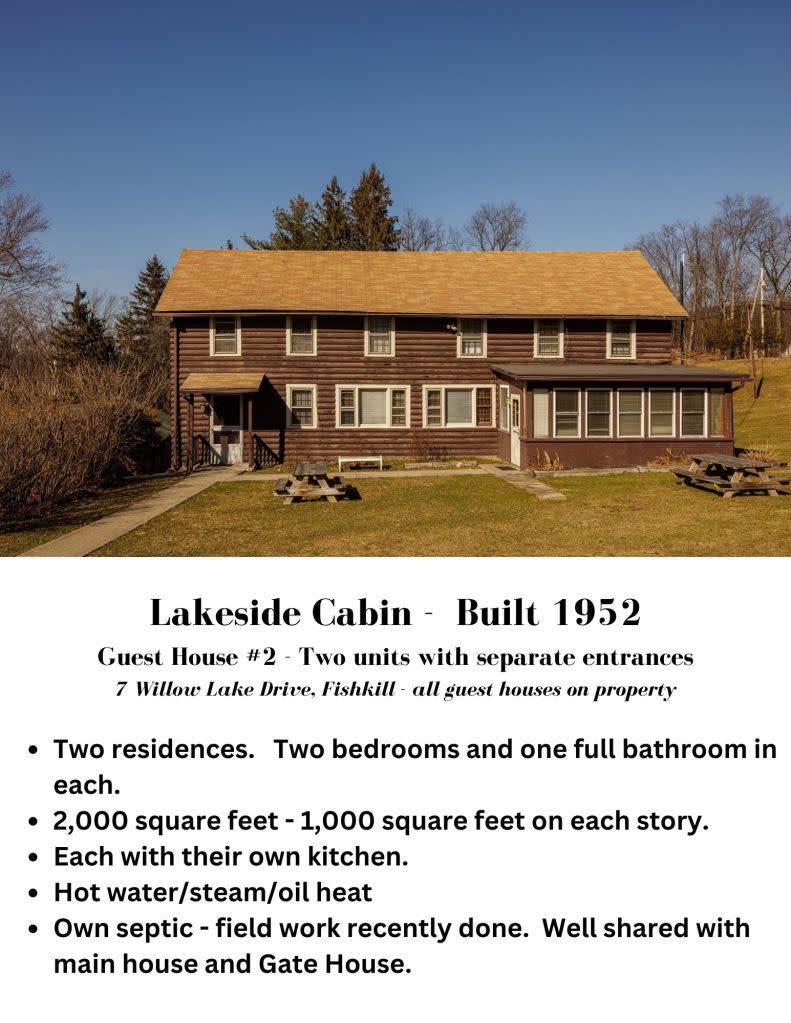

Next up, the 1952 Lakeside Cabin, a smaller two-family, followed by the Cottage from 1982.

The latter 1,280-square-foot two-bedroom, one-bath has a woodburning fireplace, electric heat and a detached screened-in porch.

Near the Cottage sits a gazebo shaped like a witch’s hat built over a giant 1800s water well. Off in the woods are a century-old fish hatchery and stone walls dating to the Revolutionary War era.

There are lodgings for animals, too, plus a creek with stone bridges and ample foot trails.

Perhaps the most interesting feature on the property, however, is Tree Tops, a writer and artist’s studio built at the edge of a hill, giving the feel of a giant tree house.

“The magic is real here,” Park said while driving a patient golf cart over large tree roots. “You can feel it.”

She noted that the current owners have done various updates in the last 20 years, but sections of the main and guest houses visibly need some work. What it lacks in new qualities, however, the property makes up for with potential.

Located near the river towns of Beacon and Cold Spring, and just an hour and a half from Manhattan, it could be a family compound, short-term rental site or a wedding venue, Park said.

“It comes down to how a buyer is intending to use it,” she explained, but “every person that’s come here has loved it.”