After the recent extraordinary show of force defending changes to LLPAs by federal regulators and their friends, the forest through the trees risk remains in focus to me.

One of the great concerns I have, as both a former regulator and the former head of a major industry trade association, is the downside risk of keeping the GSEs in conservatorship any longer. For me, it’s really a question about the lesser of two evils.

What’s the greater risk to housing: an endless series of FHFA directors who change seats with each political administration and then proceed to tinker with policy in pursuit of political priorities? Or, the risk of releasing Fannie and Freddie without firmly legislating some of the reforms that I and many others advocated for, going back to the early years of conservatorship?

Make no mistake about it, I sat firmly entrenched for years opposing the “recap and release” crowd, to the point where the camps on both sides of the issue were in almost pitched warfare. The Mortgage Bankers Association argued that Congressional reform should precede any effort to release the GSEs. In fact I testified in front of Congress in 2017 stating such.

But today I now see the risks of letting this drag on into perpetuity without resolve. As each succeeding FHFA director comes into the role the industry, potential homeowners, lenders and more will face the risk of a cascading series of policy initiatives being implemented by the GSEs at the behest of the FHFA, regardless of whatever protests that may come from the respective staffs at either GSE.

While the latest was this clearly manipulated LLPA pricing structure and the now failed attempt at a DTI cap, the list of fees added to 2-4 unit homes, second homes, cash-out refinances, and more appear to be focused on political objectives and not actual risk.

In fact, MBA traditionally argued that g-fees and other pricing methods at the GSEs should only reflect the actual risks of the loans and not be used for other purposes. Prior to the collapse of Fannie and Freddie, pre 2008, the GSEs would give preferred pricing to their largest sellers in what was known as “alliance” agreements. The spread in pricing between a large seller and a small one was significant.

I remember early in my career at MBA taking three CEOs of independent mortgage banks to meet with then Acting FHFA Director Ed DeMarco to argue against any price disparity based on anything but the actual risk of the loan. And DeMarco responded, almost completely eliminating the pricing differences during his tenure.

But today we have more to be concerned with. You see, the LLPA changes, while small in impact, were just part of the slippery slope of adjusting fees and policies to make the GSEs do business differently and to get them to focus more on entry-level homebuyers.

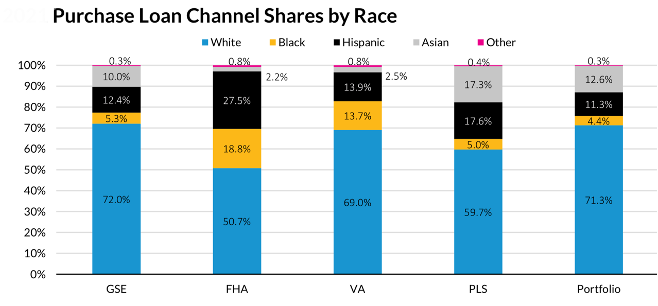

The Urban Institute puts out a monthly chart book that is chock-full of incredible data about our marketplace. In the most recent May release, they show just how hard it is for the GSEs to expand access to minorities who make up a significant share of new first-time homebuyers.

As the chart above shows, it’s the Ginnie Mae programs, FHA in particular, that completely dwarf the efforts of the GSEs in this regard. And while these modest changes to LLPAs might help, there is far more that impedes the ability of the GSEs to be effective in this area.

But FHFA hasn’t stopped there. There is the implementation of goals focused on LIP (low income purchase loans) and VLIP (very low income purchase loans) that could result in a number of unintentional distortions to pricing and credit availability. It’s all in their affordability goals and, while complicated, we can already see distortions.

The goals, shown in the chart above, are clear, but if you look at how the GSEs have performed historically against these numbers, the fact is that there are many years over the last decade where these goals would have been missed.

But now things are changing. The GSEs are using the cash window to buy more of these LIP and VLIP loans, reducing the effectiveness of the cash window for other purposes. We are seeing the GSEs begin to selectively reduce the volume of high-balance purchases in order to improve the percentages.

Over the course of 2022, it appears that Freddie may have begun offering selected customers pricing incentives for lower balance owner-occupied purchase loans and also allowed customers with greater numbers of these loans to increase their delivery percentages.

Fannie Mae, on the other hand, seems to have required customers to simply deliver a representative mix of VLIP and LIP loans to both GSEs. Since Fannie Mae had lower delivery percentages with selected customers that had more of the lower balance loans, they believe they did not meet some of the enterprise housing goals for 2022.

The need to hit the targets is forcing the GSEs to reduce the ability of sellers to deliver what the market will bear and instead deliver to the mix the objectives that they need. The problem here is that they are turning to negative incentives.

Facing a market that is not producing loans at the aspirational levels of the current VLIP and LIP goals, the GSEs appear to have turned a corner. They are transitioning from positive incentives that might promote greater production of housing goals loans, to now imposing disincentives, from both a pricing and volume perspective, that create an adverse impact on a significant majority of GSE owner-occupied purchase borrowers.

Said differently, the GSEs are not able to produce enough VLIP and LIP “numerator” loans, so they have no alternative but to try to reduce the non-VLIP and LIP “denominator” loans in an effort to achieve the ratios that FHFA established.

Look, the GSEs have always had affordable housing goals. What has changed is that they no longer have a retained portfolio that can be used to help meet these goals through bulk purchases. But more importantly, this new structure is forcing pricing distortions which we are already seeing blatantly though the LLPA structure, but even more so through changes to usage of the cash window, disincentives to sellers to reduce higher balance loans, and more.

All of this will lead to hurting the mainstream borrowers that the GSEs have always served.

As shown above in the chart showing the GSEs’ mix to other sources, perhaps we need to think differently here. Yes, reasonable goals make sense for the GSEs. But all the programs within Ginnie Mae still dwarf any ability the GSEs have to significantly change the market.

But the greater question we all need to ask is this: is the lesser of evils the need to release the GSEs from conservatorship and allow them to return to a more self-managed business environment? This would lessen the ability of their regulator to use these two companies for political purposes, which might distort the market in ways that are ultimately more harmful than any gains they may make along the way.

For me, I have turned this corner. The GSEs are far too important to be overly manipulated in ways that might hurt execution for the traditional homebuyer in these programs. There are other ways to explicitly support affordable housing objectives. This to me is just too slippery a slope.

As I see the forest through the trees, I am faced with a new conclusion. We need to release the GSEs from conservatorship as soon as possible. There is too much at risk to the housing finance system over time as we erode their core business models for political purposes.